Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills: A Feminist Art Commentary

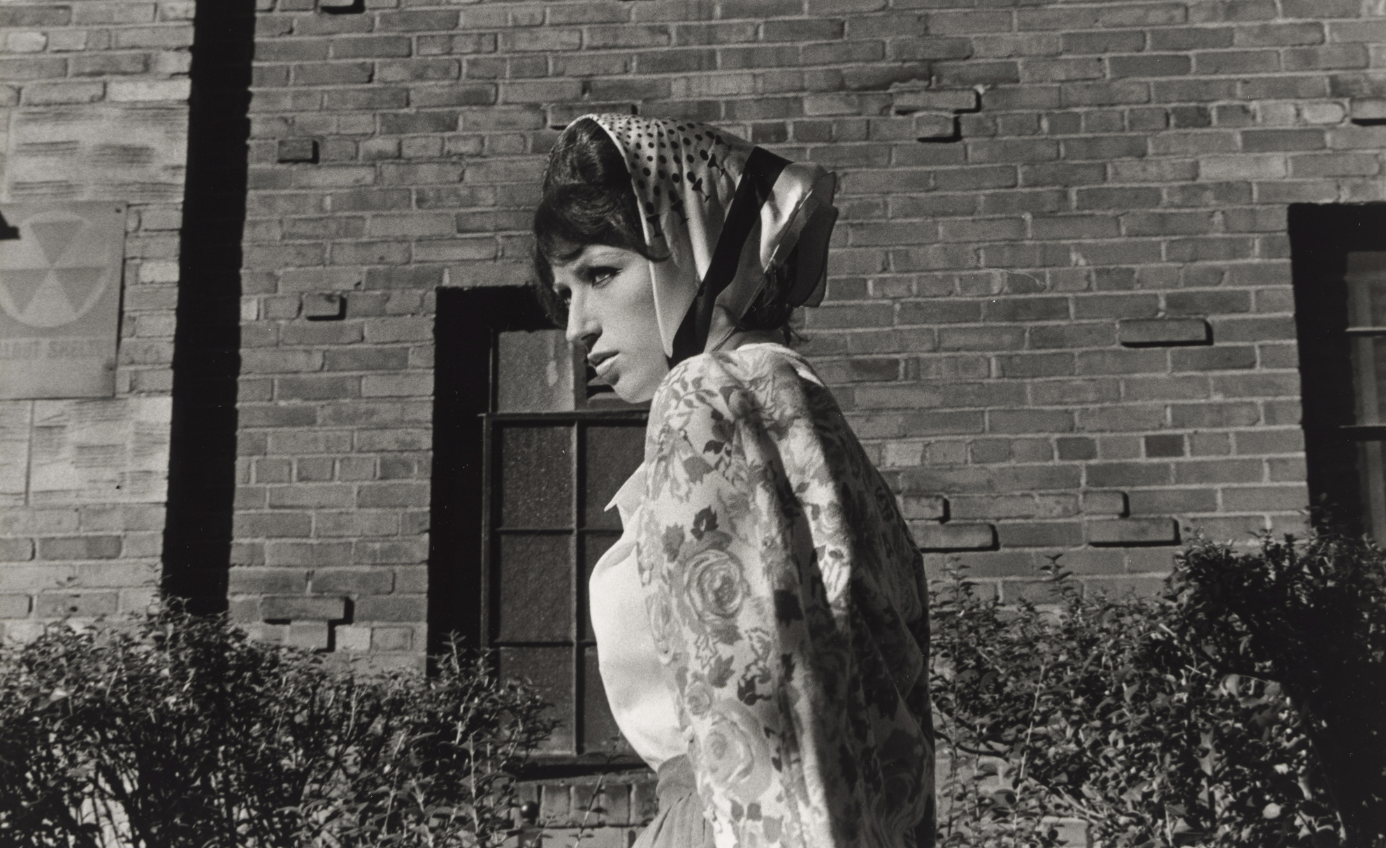

This blog was originally written in 2017 as an academic paper

Untitled Film Still #92

Cindy Sherman began her artistic career by using her likeness to take photos that challenged the female stereotype portrayed in the media. Although her collections have been a great success as a whole, not all of her pieces have been well received. Sherman’s artwork has, at times, been seen as controversial and even opposed to the feminist movement. This blog will analyze the message and artistic style behind Cindy Sherman’s photographs, discuss the controversy behind several of her pieces, and explain how her photographs impacted both society and the feminist movement. All of this information will help clarify the true intention and purpose of her artwork.

Many artists attempt to create art that evokes an emotional response from the viewer. Art can be seen as their expression of inner ideologies, and Sherman’s photography is no different. Growing up amidst the American Woman Movement, a time with many political campaigns for reforms on women’s issues, Sherman sought to challenge the stereotypical portrayal of women in the media through her art (Rosenberg, 2017). This commentary on women in the media can be seen in her first official photograph series known as The Untitled Film Stills.

Untitled Film Still #03

The photographs featured in this series show an array of women in society, taken from low vantage points that have the viewer looking up at the subject. Additionally, “Sherman and her generation learned to see through mass media clichés and appropriate them in an ironic manner that made viewers self-conscious about how artificial and highly constructed "female portraiture" could prove on close inspection” (Rosenberg, 2017). These photographs were meant to make people aware of and question female portrayal in the media. Untitled Film Still #21 is a successful example of this, showing how culture had become largely a game of theatrical posing (Rosenberg, 2017).

Untitled Film Still #21

This photo features Sherman dressed up as a woman in the city, with an indecipherable expression on her face. She seems to be aware that she is being observed and concerned with the judgment of others around her. These Untitled Film Stills were the first well-renowned photographs produced by Sherman and placed her in the spotlight, allowing her to expand on ideas of feminism and appropriation of women in society.

The subject of Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills series brought about a debate among critics and fans alike. Of the photographs displayed, Sherman was the subject of each, or so it seemed at first glance. “Although she poses for her photographs, Sherman’s pictures are not self-portraits in a traditional sense” (Biography). Not being the subject was a conscious choice by Sherman, as she wanted to show a perception of women and not her actual self. Her work encouraged self-reflection and made people recognize something within themselves when viewing her photographs (Cain, 2016). She was not the subject of her photos, but rather the female identity in general.

Untitled Film Still #84

The constructed vision of women was something that Sherman sought to break down and dissect. To make people aware of this social construct required the deconstruction of female stereotypes. “To model in several roles, she reveals gender as an unstable and constructed position” (Cain, 2016). This idea of photographing one’s self without being the actual subject causes viewers to take a step back and consider the meaning behind the piece. Her work has clearly influenced the art community, as her pieces are still a topic of debate today.

Cindy Sherman’s earlier photographs were conversation starters that brought awareness to feminist issues, however, not all of her photographs were widely accepted upon creation. There is a discussion in the art community about whether or not some of Sherman’s photos and other pieces of art are controversial to the feminist movement. One still in her original series, Untitled Film Still #30, shows a grisly and disturbing image of a woman in distress (Cindy Sherman, 2017).

Untitled Film Still #30

Although her other photographs had also shown general stereotypes of women in society, this particular photo was not as well received. “Sherman portrays herself in the disturbing guise of a woman who has been battered, showing just her head as she looks out at the viewer, bewildered and crying, with her makeup running down her cheeks” (Greenberger, 2013). The photography is staged, which causes the viewer to question what Sherman wants us to see. Like her other photos, is this a comment on women in society? Is this a metaphor for how women are treated in the media, beaten down by societal standards?

This photo sparks some controversial debate around abuse and whether or not she is appropriating such treatment of women. An argument for that would be to question whether images of beaten women should be sold and shown to the public. Although it is not believed that appropriation was her true intention, this is still a topic of debate, as with any work dealing with a sensitive subject would be. This photograph is only the beginning of Cindy Sherman’s controversial artworks, shortly followed by her Fairy Tale Series.

Untitled Film Still #152

Throughout most of Sherman’s career, she used her likeness to portray an idea of women in society. Taking a step out of her comfort zone, the Fairy Tale Series is the first to feature dolls and prosthetics as subjects rather than herself (Cindy Sherman, 2000). This series proved to be a pivotal and yet another controversial point in her artistic journey. “Fairy Tales are also the first pieces that go beyond the contemporary stereotypes of women” (Cindy Sherman, 2011). By taking herself and her likeness out of the photos, the audience is forced to confront the subject matter directly.

The images that Sherman displayed in this series are different than what people were accustomed to. “The viewer is confronted by images that tackle mortality and fear through setups of gruesome crime scenarios that include human excrement and vomit” (Olive, 2012). Rather than comment on societal images, this series targets the hidden fears and cruel reality of the world. This type of setting leaves the viewer uncomfortable and upset rather than with a sense of happiness and peace; an ironic reaction, as most fairy tale stories end with a happily ever after. The controversy and irony behind these images reveal yet another attempt to comment on societal norms and shatter superficial expectations. Through this Fairy Tale Series, Sherman successfully expressed the message that not everything is as it seems on the surface.

Untitled Film Still #474

Artists often create pieces of art that are relevant to the period they are in, which has an impact on those who view them. An artist’s work can be a reaction to mass media projection or a comment on societal norms. Cindy Sherman set out to do both through her photography. She created her photographs to comment on the mainstream views and opinions that society holds, while also criticizing their viewpoint. Throughout her career, she has created images that touch on the portrayal of women in the media, the fanaticized idea of fairy tales, and even the portrayal of aging women in society, as seen in Untitled #474 (Hoban, 2012).

Her work not only comments on the current society but also foreshadows what is to come. “Her work has in some ways presaged the media age that we live in now and also responds to it…she was one of the first to explore the idea of fluidity of identity” (Olive, 2012). Before the age of Photoshop, Sherman was formulating manipulated images to create an alternative reality. This style of photography impacted later artists, who still draw inspiration from her work today. Jillian Mayer uses a Shermanesque style in her photographs and speaks highly of Sherman’s early work: “She was the trendsetter in terms of distorted characters within self-portraiture” (Hoban, 2012). The term Shermanesque is loosely referred to in the art community as photographs that are self-portraiture, portraying a character that is not of them, while also occasionally featuring some abnormality. The fact that artists are still experimenting with photos in the style of Cindy Sherman, decades after the style began, shows that her work has had a tremendous impact on society.

Untitled Film Still #70

Sherman’s photographs not only impacted contemporary artists but also influenced the feminist movement. As mentioned earlier, her portrayals of women in media, fairytales, and the aging process have been generically labeled as feminist art. Commenting on her work, Sherman said, “The work is what it is and hopefully it’s seen as feminist work or feminist-advised work” (Berne, 2003). She knows that her photographs have been analyzed according to the feminist movement, however, she leaves this interpretation up to the individual.

This interpretation is quite easy, as most of her photos require the viewer to look up at the female subject, which makes the subject automatically appear dominant (Easton, 2012). Sherman goes on to elaborate on this feminist state of mind by saying that feminist ideology was the normality when she was growing up. Discussing feminism, however, was never an open topic for people in her generation; it just was what it was (Berne, 2003). This viewpoint of inherent feminism might have helped propel the success of Sherman’s work regarding the feminist movement. Her relevancy to feminism could not be more prevalent, as her artwork continues to be referenced as a key supporter of the movement.

Untitled Film Still #19

In conclusion, Cindy Sherman created revolutionary art that challenged mainstream society and caused people to take a step back and analyze the meaning behind her photographs. Although the interpretation of her images has changed throughout the years, her instinct to confront the viewer and challenge viewpoints has remained a concrete theme throughout them all. This confrontation initially caused people to question whether or not her work supported or criticized the feminist movement, although the support of feminism was the artist’s true intention. I believe that Cindy Sherman created a revolutionary style of art that caught previous generations off guard and will continue to inspire artists of future generations to branch out into uncharted territories of creativity, commentary, and expression for years to come.

References

Berne, Betsy. "Studio: Cindy Sherman". Tate.org.uk. N.p. 2003. Web. 14 Apr. 2017. http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/studio-cindy-sherman

Biography. (n.d.). Cindy Sherman - Photographer, Model, Director, Actor, Avant-Garde Images, Doll Parts and Prosthetics, Movies. https://www.cindysherman.com/

Cain, Abigail. "Is Cindy Sherman A Feminist?" Artsy. N.p. 2016. Web. 12 Apr. 2017. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-is-cindy-sherman-a-feminist

"Cindy Sherman". Mmoca. N.p. 2011. Web. 17 Apr. 2017. http://www.mmoca.org/mmocacollects/artworks/untitled-film-still-30

“Cindy Sherman”. Moma. N.p. 2017. Web. 15 Apr. 2017. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/56618

"Cindy Sherman". Skarstedt. N.p. 2000. Web. 11 Apr. 2017. http://www.skarstedt.com/exhibitions/2000-05-06_cindy-sherman/#/images/2/

“Cindy Sherman: "Untitled Film Stills" (1977-1980)". American SuburbX. N.p. 2014. Web. 7 Apr. 2017. http://www.americansuburbx.com/2014/12/cindy-sherman-untitled-film-stills-1977-1980.html

Easton, Martha. "Feminism." Studies in Iconography 33: JSTOR 99-112. 2012. Web. 7 Apr. 2017. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2392427?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Greenberger, Alex. “The Dark Side of Cindy Sherman.” Art Space. 2013. Web. 8 Apr. 2017. http://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/art_market

Hoban, Phoebe. "The Cindy Sherman Effect". Art News. N.p. 2012. Web. 12 Apr. 2017. http://www.artnews.com/2012/02/14/the-cindy-sherman-effect/

Olive, Lily Koto. "Cindy Sherman: Moma’s Career Survey Of Photography’s Shape Shifting Chameleon". Art-rated. N.p, 2012. Web. 14 Apr. 2017. http://art-rated.com/?p=501

Rosenberg, Bonnie. "Cindy Sherman Biography, Art, And Analysis Of Works". The Art Story. N.p, 2017. Web. 8 Apr. 2017. http://www.theartstory.org/artist-sherman-cindy-artworks.htm

Sherman, Cindy, and Goldsmith, David. “Cindy Sherman." Aperture, no. 1993: 34-43. Web. 10 Apr. 2017.