Beneath the Surface: Diving into the Birch Aquarium's Interactive Learning Spaces

This blog was originally written in 2023 as an academic paper Analyzing Core Functional Areas of the birch aquarium at scripps

Aquariums welcome visitors from various demographics to view and discover mysterious underwater ecosystems. This is an exciting invitation to learn more about creatures rarely seen in day-to-day life. Although aquariums attract over 200 million visitors worldwide, more than the NFL, NBA, NHL, and MLB annual attendance combined, their success is dependent on the ability to connect with visitors, promote conservation efforts, and inspire positive action (Visitor Demographics). How an aquarium organizes its collections, exhibits, and interpretations affects the experience and messages people take home with them. A strong mission is the foundation upon which an aquarium is organized and influences how information is presented to visitors. Drawing on my visit to the Birch Aquarium at Scripps in La Jolla, California, this paper will analyze how effective the institution is at connecting with visitors and how its offerings communicate the overarching goal of promoting conservation and ongoing research.

The Birch Aquarium’s mission is simple: “Connect understanding to protecting our ocean planet” (Birch Aquarium). Working with the Oceanography Institute at the University of California, San Diego, the focus of the Birch Aquarium at Scripps is to showcase discoveries by scientists on climate, earth, and ocean science to all who enter its facilities.

The phrase “connect understanding” underscores a priority on teaching, and encouraging learning moments with visitors of all backgrounds and ages. This connection can be seen often throughout the aquarium, with the incorporation of staff who foster interactive learning moments, interpreting knowledge discovered by biologists. This idea of the aquarium as a welcoming space is further emphasized in its value statement, encouraging people of all types to ask questions and interact with oceanography scientists (Birch Aquarium). The tail-end of their mission, “protecting our ocean planet” conveys a collective effort to preserve and conserve natural ocean habitats.

This concise mission statement is the basis for all decisions made and impacts the collections, exhibitions, interpretive elements, programs, and various educational opportunities offered. At the Birch Aquarium, these aspects are heavily influenced by the institute’s research and conservation programs. Although conservation education is an important part of their mission, this is not usually at the top of most visitors’ to-do lists for their visit, so the message must be conveyed in a fun, engaging manner (Packer, 2010, p 25). The aquarium currently prioritizes its efforts on seadragon breeding and both seahorse and coral conservation. With these ideas in mind, one can assume a visit to this aquarium will be unique and highly educational.

Driving up to the Birch Aquarium, it’s impossible to miss two features: being welcomed onto the UCSD campus, and the gorgeous ocean view. These are strong indicators to guests that they are in the right location to learn more about the ocean. Outside the aquarium, visitors are greeted by two large statues of whales. Although they do not own or display any whales inside, these impressive structures are meant to cause wonder and excitement before walking into the main building. Inside the aquarium, the emphasis is on the exhibits and small interactive learning stations peppered throughout the space.

Unlike aquariums of recent development that rely on attractions, animal shows, and the always impressive tunnel to “wow” visitors, the Birch Aquarium sticks to its scientific roots and focuses on inspirational learning opportunities paired with self-led discoveries. This type of format helps create a quasi-wilderness experience for visitors, where they can “connect emotionally with animals as if they were encountering them in nature” (Linquist, 2018, p 333). Designed around a central lobby with entrances to several exhibit areas, one can choose a path based on personal interest.

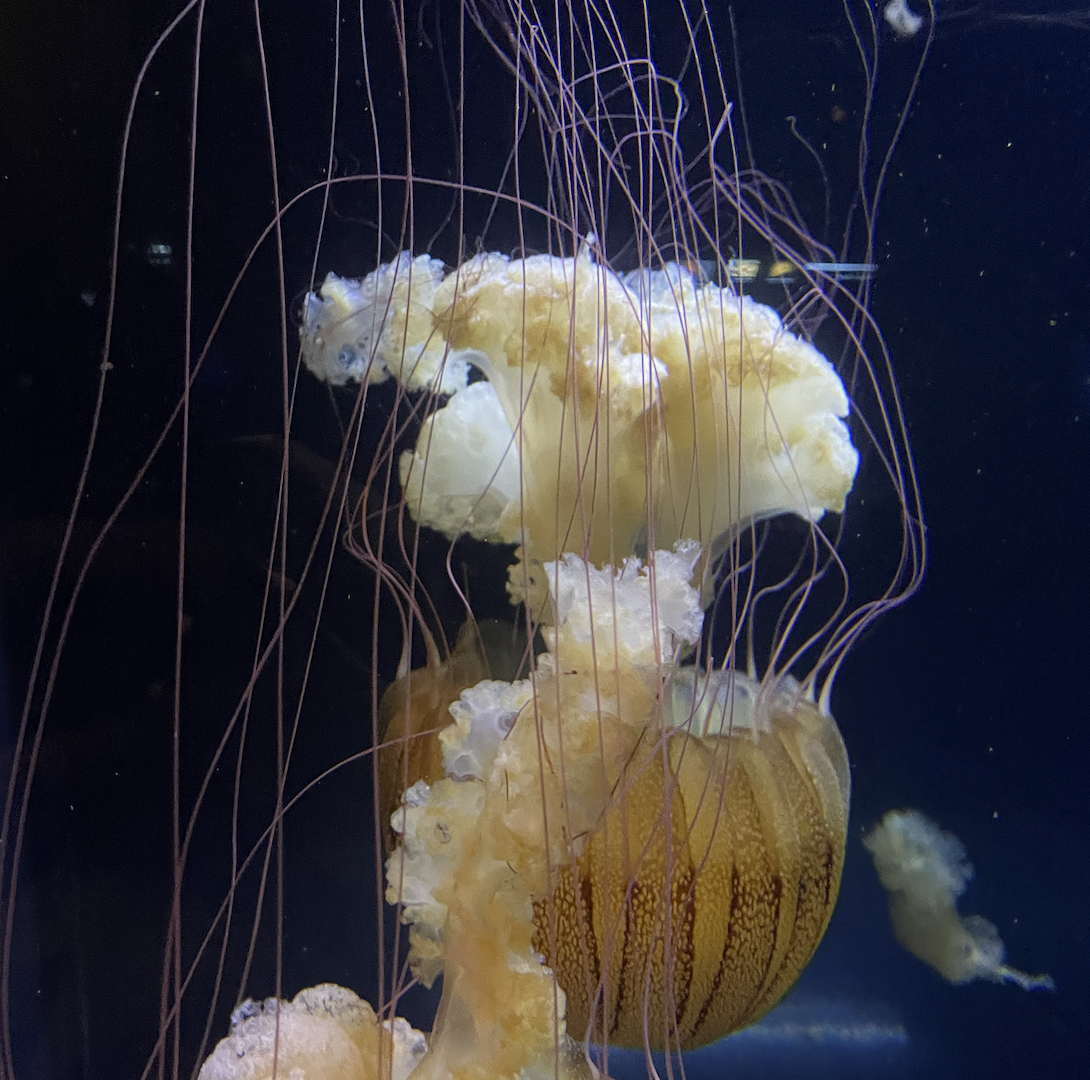

To the left, there are penguins, seahorses, sharks, and a “hidden heroes” exhibit, while on the right is the hall of fishes. Creatures on this side are sorted into various tanks based on local, natural habitats. This method of planning exhibits around themes and regions as opposed to displaying fish from around the world is a common element in newer aquariums (Taylor, 1993, p. 10). Last but certainly not least, in front of the lobby is a grand view of the ocean which draws people towards an outdoor space with tide pools and several touch stations.

Once in line for the tide pools, guests can choose to look at the gorgeous view, read more information about the animals on signage, or chat with knowledgeable volunteers. Offering information in a variety of ways like this provides experiences for people with multiple interest levels and is intended to “increase the visitor’s interaction with the scene in front of them” (Ramberg, 2002, p. 307). While touching a sea cucumber, I was able to talk with a staff member about where they come from, what they usually eat, and how they survive in the wild. Guests of all ages and backgrounds were encouraged to participate and it seemed to excite everyone around me. There is a “general belief that the unique experience of touching or interacting with an animal will help create conservation awareness by facilitating caring about animals and their habitats”, so the fact that there are multiple touch stations throughout the Birch Aquarium shows their commitment to promoting conservation (Rowe, 2012, p. 1). In total, I was able to touch a baby shark, sea cucumber, sea star, snails, and little cleaner shrimp.

Back inside, a large video plays on one wall of the lobby describing the building’s infrastructure and piping systems. In the video, scientists from the Oceanography Institute are introduced and clips of behind-the-scenes areas where water is tested before cycling back into the system are shown. The size and placement of this is important, because more than any other exhibit medium, video can convey emotion and influence attitudes (Ramberg, 2002, P. 310). This video is meant to draw people in, introduce them to the faces taking care of the aquarium, and explain all the hidden work that goes into its day-to-day operations. Transitioning back into this main lobby area forces visitors to decide on which path to take, to the penguins, seahorses, and hidden oddities discovery area, or through the hall of fishes.

I decided to check out the penguins first, as I’d seen several photos of them on the aquarium’s website and knew I would enjoy it. This penguin exhibit has only one entrance and exit, so after walking through, people must turn around and head back where they came from to access to rest of the aquarium. This did not seem like the best use of traffic flow to me, and I can understand how people can be confused about how to access the penguin exhibit if they miss the only entrance. It seems the aquarium anticipated this issue and placed a map in a location where many tend to get lost. The map shows a dotted red path people can take to go back around and enter the exhibit.

While this map was helpful, I wondered what logistical issues caused this layout to exist. As most aquariums are built custom to accommodate their specific needs, this feels planned into a space that already exists. Research I pursued after my visit indicates that this particular exhibit opened just in 2022 and that the penguins were brought on as “part of an international Species Survival Plan that works to maintain the genetic diversity of certain species in zoos and aquariums” (City News Service). The decision to add this exhibit to their signature offerings was heavily influenced by scientific expertise at the research institution and the aquarium’s commitment to sharing ongoing scientific discovery (Birch Aquarium).

Birch Aquarium is the only institution in the Western U.S. to house these birds and they attribute the addition to bringing attention to the important role that these animals play in our ecosystem. Although the penguins initially feel out of place, the sharing of research and novelty in this exhibit make sense in the larger picture of conservation and communicating the negative effects that climate change is having on their natural habitat. The aquarium’s mission to educate and inspire continues in this exhibit as a volunteer waits to help people touch fabric that mimics what it would actually feel like to pet a penguin and tells stories about all the birds on display.

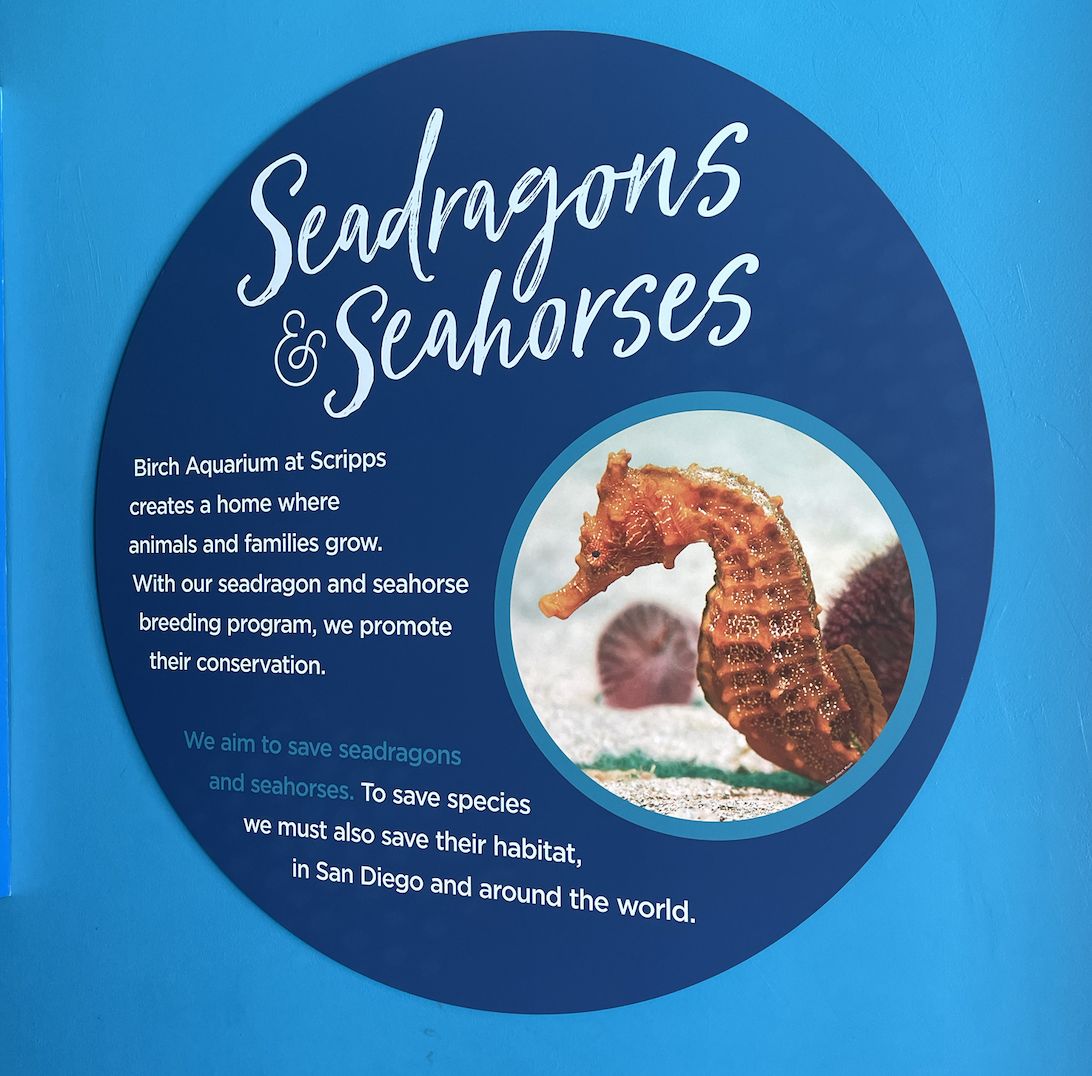

Retracing my steps, I make a U-turn in the lobby and check out the seahorse and weedy seadragon exhibits. This is an extensive section with a mix of signage and videos alongside several tanks with various species of seahorses. A main sign reads, “Birch Aquarium at Scripps creates a home where animals and families grow”. There is an emphasis on saving species and natural habitats, which extends the subtle, continuous theme of conservation. Everything an aquarium does “must ultimately contribute to a conservation outcome”, so it can be inferred that all interpretational points here were created with this in mind (Ramberg et al., 2002, p. 313).

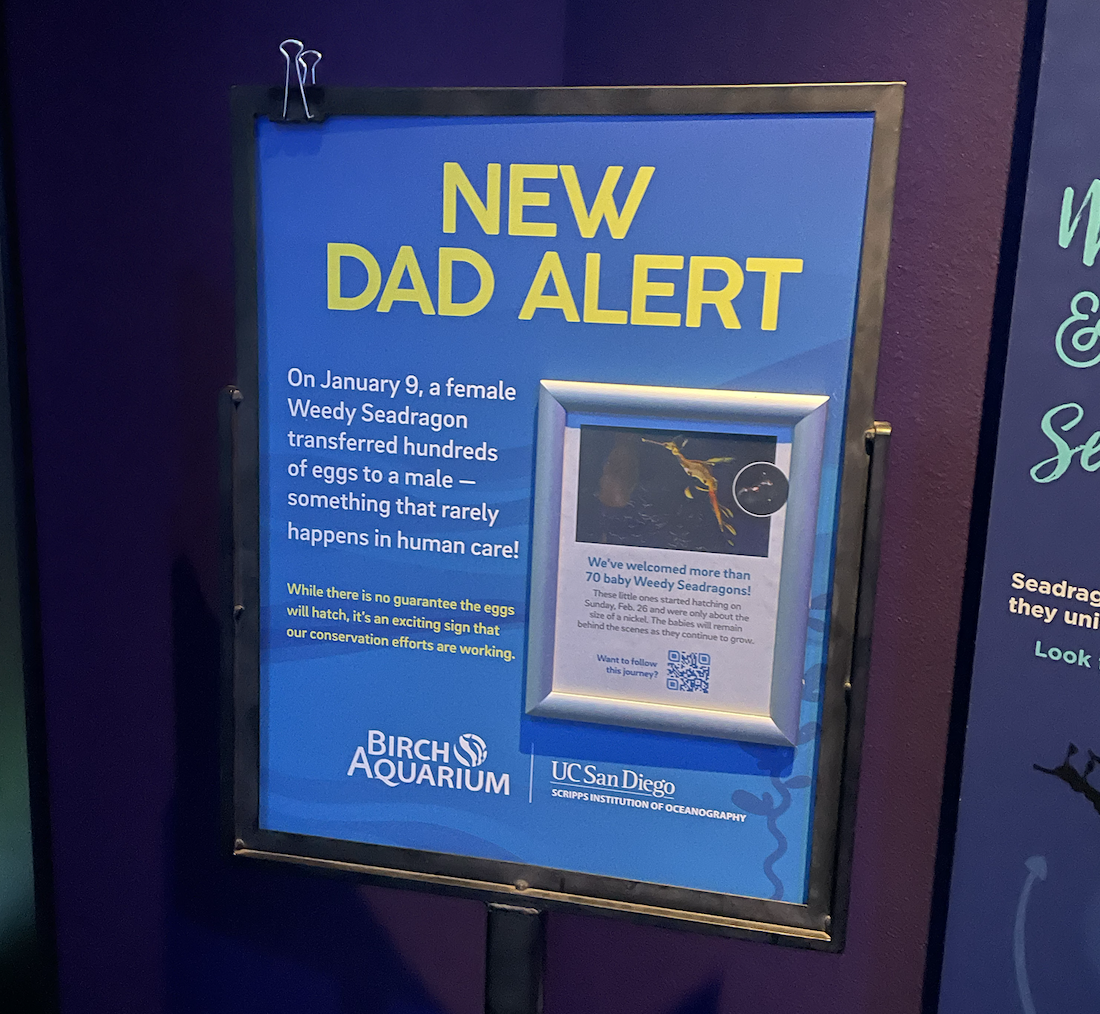

Across from a large tank of seahorses, there is a video playing on a loop of a male seahorse giving birth. Using this combination of media to inform the visitor reflects the most effective way the Monterey Bay Aquarium found to convey its main point: by “reinforcing the message in different modes for visitors with different learning styles” (Ramberg et al., 2002, p. 310). Another instance of signage next to tanks and a video screen is in the weedy seadragon area. There, the aquarium built a special, tall tank to accommodate the weedy seadragon’s unique mating ritual. It was noted that the curator of this exhibit traveled to their natural habitat in Australia to gather inspiration for the design of this enclosure.

The aquarium’s ultimate goal with this exhibit was to create the perfect conditions to encourage breeding in captivity. Although this is a difficult task, the team’s hard work paid off with their first successful hatching in 2020 (Birch Aquarium). Today, just to the right of the tank is a live feed of 70 baby weedy seadragons that were born in early 2023! This positive feedback shows the aquarium that it is successful in its efforts to preserve the species. This area left me feeling inspired and as if my visit was contributing to the advancement in knowledge and care for the species.

After the seahorses and weedy seadragons, I’m transported into a comic book-style space called “Oddities: Hidden Heroes of the Scripps Collections”. This area is quite a transition from the seahorse area in terms of design, which brought life and excitement to those around me. Labels here are bigger, brighter, and louder, and focus on action words to draw people in.

Here, visitors have a mix of interactive options like taking photos, looking at 3D models on tablets, operating microscopes, or touching small shrimp in a tank. Everything presented here advertises a specimen’s “superpower” and successfully provides visitors with the most popular information they wish to learn at aquariums, which are odd facts and behaviors (Fraser et al., 2020, p. 13). Online, it’s stated that in this area “guests will learn what it takes to collect scientific samples and have the opportunity to test out some of these unique adaptations through superhero cosplay” (Birch Aquarium).

Organized by superpower categories like vision, glow in the dark, and strength, the viewing of specimens in jars provides a more scientific feel to the aquarium. Each section encourages discovery and wonder, which “provides direction and impetus for environment education in early childhood” (Wilson, 1996). Ending this section are three different media elements along a corner wall, all relating to coral reefs and the conservation issues surrounding their depleting natural habitats. Although images and videos like this can be discouraging, the aquarium ensures that clips of actual scientists researching coral health are intended to “support coral ecosystems around the world”. The running theme of conservation is consistently accompanied by a current example of how aquarium staff are directly working to combat the negative effects of climate change and habitat deterioration.

At the end of this exhibit, double doors lead to an outdoor space with another stunning view of the ocean. Here is the spot mentioned earlier where many visitors must attempt to access the penguin exhibit because there is the sign explaining directly how to get back there by retracing steps. This outdoor area is open with many tables, which encourages families and visitors to interact or relax outdoors. Spaces like this provide an area for those more interested “in the social and restorative aspects of their visits” (Packer, 2010 p. 26). After taking in the view, I was surprised to see that the shark exhibit was smaller than I anticipated. Only viewable outdoors, a tent covers the top and sides while the tank itself only includes sand with concrete walls.

I immediately wondered why this exhibit seemed bare compared to the others, especially since tanks are typically designed to look like a creature’s natural habitat to encourage natural behaviors and lure the visitor into another view of the world (Taylor, 1993, p.10). Out of all the areas in the Birch Aquarium, this is where I thought they could improve the most in terms of habitat design - but further research after my visit indicated that this simple enclosure is intentional.

This tank was created to hold local marine life like reef sharks, who are accustomed to the bare, sandy shores of La Jolla (Birch Aquarium). Here, a volunteer is present with a few shark skulls and teeth for us to touch and welcomes everyone to feel the objects. Moments like these help move interactions into deeper consideration of the animals and the work being done to help them (Rowe, 2012, p. 75). Traffic flow is directed one way to the exit where a photo opportunity awaits within a larger-than-life shark head. These opportunities to take and post photos from the aquarium pop up several times throughout my visit and exemplify the aquarium’s effort to promote engagement in-person and online.

Officially complete with two-thirds of my visit, I head back across the lobby to the hall of fishes. Traffic flow on this side is intended to a one-way, pre-determined path. This is unlike other areas which felt like distinct sections placed next to one another. Journeying through this section provides visitors with a “self-guided tour of marine habitats found along coastlines and beyond, from the North Pacific to the warm tropics of Mexico” (Birch Aquarium). Here, visitors are primed to notice small differences between tanks as they move through the ecosystems and view interpretations in the form of signage, infographics, images, and video screens.

Once again, this use of multimedia to portray messages allows for people of all interest levels to absorb knowledge during their visit. “Because learners have so much choice regarding what, where, when, how, and with whom they learn, such experiences are often referred to as 'free-choice learning’” (Packer, 2010 p. 26). I notice the use of aquarist notes here, which provide refreshing, fun facts on various tanks and make it feel as if a biologist is traveling through the aquarium with me dropping unique tidbits of information (Figure 4). These labels mimic what the Monterey Bay Aquarium found to be successful: telling stories, pointing out interesting facts, answering pre-determined questions, or pointing out what a visitor is seeing (Ramberg, 2002, p. 306).

Before arriving at the end of the hall, I’m greeted by a floor-to-ceiling view of a 70,000-gallon kelp forest. Here visitors come face-to-face with a typical kelp forest found in San Diego with “no dive gear necessary” (Birch Aquarium). This type of immersive experience is unique to aquariums and designed to “provide opportunities for visitors to get as close as possible to the animals, or see the animals from a new and different perspective” (Packer, 2010, p. 31). There is plenty of seating for visitors to sit and enjoy the tank, and I can envision educational talks or tours using this space to connect their purpose with the actual animals.

Ending this section is a special tank focused on corals, explaining how the Scripps Oceanography Institute reduces its need to collect coral from the ocean by fragmenting their own, growing it, and sharing it with other institutions. This method of coral gardening provides a sustainable take on reef restoration, so long as the “coral survives and the related fishery is managed properly” (Penning et al., 2009, p. 8). Over the years, the Birch Aquarium has given hundreds of coral fragments to institutions worldwide, proving the success of the program and its efforts to reduce pressures on wild populations.

Along with exhibits showcasing local species and highly interactive learning stations, the Birch Aquarium also offers additional educational opportunities in the form of lectures, guided walks, summer programs, and behind-the-scenes tours. These programs help deliver conservation action messages by modeling the behaviors the aquarium hopes visitors will adopt (Ramberg, 2002, p. 315). Taking advantage of these offerings, I decided to participate in a one-hour behind-the-scenes seahorse tour.

Here, five visitors (including me) were guided through the seahorse exhibit and given an intro lesson about the aquarium’s breeding program, the planning of the seahorse exhibit redesign, and how students at UCSD are advancing species research. Through a door marked for employees only, we entered the kitchen where animal meals are planned and prepared. According to the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the food used to feed collections must be from “sustainable, disease-free sources” (Penning et al., 2009, p.6). Most of the seahorses here eat brine shrimp, and the aquarium had to discover which species would tolerate frozen food versus those who preferred live feedings.

On the tour, I learned that the aquarium does its best to grow its shrimp for feedings, but will import from a partner aquarium in Florida when necessary. Growing its own shrimp as often as it can provides a sustainable source of protein for the seahorses. After viewing the food prep area, our guide leads us to a secured room where all the seahorses that are not on display are kept. In this smaller room, several tanks of various seahorse species are kept either in quarantine, as a transition from one habitat to another, or for monitoring purposes. Each of us is allowed to drop a spoonful of frozen shrimp into one tank, and we watch as seahorses suck in their meal.

Although most of the information shared with us during this tour was pre-planned, spontaneous questions from visitors provided authentic and meaningful conversations with our tour guide. “The intimacy of a personal encounter can’t make up for an abstract message”, so the person who leads this tour must fully understand and believe in their institution’s mission (Ramberg, 2002, p. 315). Before returning to the aquarium, we are shown how animals are safely packaged for transport, along with a map of over 200+ locations that the aquarium has shipped species to worldwide. Altogether, tour guests were able to view baby seahorses, learn about the pipes filtrating the seahorse quarantine room, and see an exclusive top view of several freshwater tanks. Learning about all the ongoing research and the level of care it takes to maintain these seahorses made me feel as if the extra money I spent on this tour directly impacts these efforts and makes a positive difference.

Operating an aquarium of this size requires a substantial budget to maintain. Although the aquarium does not offer any animal shows or special attractions to bring in funds, they do open their facilities for corporate events, weddings, social gatherings, or special events like Ocean at Night, where guests 21+ are invited to the aquarium past normal operating hours to enjoy live music, cocktails, and games amongst ocean life (Birch Aquarium). Because they are a nonprofit that channels all net revenue towards mission impact, events like this help supplement what can be raised through donations, educational programs, or selling merchandise.

Speaking of merchandise, it is hard for me to not notice the adorable penguin stuffed animals displayed in the gift shop as I make my way out of the aquarium. The importance of sustainability and conservation can be seen in the variety of products available, including reusable water bottles and toys made from recyclable materials. This store is open to everyone, not just ticket holders, and claims that every purchase helps further the aquarium's mission to connect understanding to protecting our ocean planet (Birch Aquarium). Also available in this area is a cafe with small bites, encouraging people to linger and enjoy the outdoors together. Even here an aquarium can communicate its sustainable messages by offering “fair trade sustainable marine products and the supply of cooked fish and shellfish from a list of non-threatened species” (Penning, 2009, et al, p. 35).

Overall, I would say that the aquarium’s social media and online marketing efforts properly prepared me for my visit. On their website, it is clearly stated that each guest must make a reservation for a specific date in addition to buying a ticket. Requiring reservations allows the Birch Aquarium to cap how many people enter each day, which helps in creating genuine connections with each guest. Social media shares unique information about specific animals and groundbreaking research the institute is conducting.

Creating connections extends here through the use of a photo contest, which encourages people to visit the penguin exhibit and post their own photos with a specific hashtag. Scrolling through the Aquarium’s Instagram page before my visit allowed me to get a peak at each exhibit, understand the layout of the building, and learn about their additional educational offerings. Back on their website, the Aquarium dedicates an entire section to preparing people for their visit. Here people can learn more about tickets, parking, exhibits, rules, dining options, accessibility, and more.

After reviewing the Birch Aquarium’s collections, exhibitions, and interpretations, I do believe they are successful in their mission to connect understanding to protecting our ocean planet. Among the tanks of fish and tide pools, over eight multi-media stations are serving to educate a wide range of interests and learning objectives. Although lacking in its offerings of animal shows, interactions, or attractions, multiple touch stations encourage interaction between visitors and volunteers, which fosters genuine moments of discovery and wonder.

The institution’s origin and focus on research and scientific discovery explain its lack of extravagant offerings in favor of sharing educational discoveries. Every exhibit connects to a story about how researchers at the Scripps Oceanography Institute are making advancements to combat natural habitat deterioration. “A great aquarium touches the emotions and feelings of visitors while it engages their intellects” and this is something I believe the Birch Aquarium has done successfully (Taylor, 1993, p xxii). Knowing that this institution emphasizes scientific discovery has encouraged me to keep up with their findings on social media, and hopefully return to the aquarium in a few years to see how species and their natural habitats have been positively impacted by their conservation efforts.

References

(n.d.). Birch Aquarium at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego. https://aquarium.ucsd.edu/

City News Service. (2022, November 15). Birch Aquarium Moves 5 Little Blue Penguins from San Diego to Cincinnati Zoo. NBC 7 San Diego. https://www.nbcsandiego.com/news/local/birch-aquarium-moves-5-little-blue-penguins-from-san-diego-to-cincinnati-zoo/3099860/

Linquist, S. (2018). Today’s Awe-Inspiring Design, Tomorrow’s Plexiglas Dinosaur: How Public Aquariums Contradict Their Conservation Mandate in Pursuit of Immersive Underwater Displays. In The Ark and Beyond: The Evolution of Zoo and Aquarium Conservation (pp. 329-388). University of Chicago Press.

Packer, J., & Ballantyne, R. (2010). The Role of Zoos and Aquariums in Education for a Sustainable Future. In Adult Education in Cultural Institutions. Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Penning, M. G., Reid, M. G., Koldewey, G., Andrews, B., Arai, K., Garratt, P., Gendron, S., Lange, J., Tanner, K., Tonge, S., Van den Sande, P., Warmolts, D., & Gibson, C. (2009). Turning the Tide: A Global Aquarium Strategy for Conservation and Sustainability.

Ramberg, J., Rand, J., & Tomulonis, J. (2002). Exhibit Philosophy at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Curator: The Museum Journal.

Rowe, S., & Kisiel, J. (2012). Family Engagement at Aquarium Touch Tanks. In Understanding Interactions at Science Centers and Museums: Approaching Sociocultural Perspectives. Sense Publishers.

Taylor, L. R. (1993). Aquariums: Windows to Nature. Macmillan General Reference.

Visitor Demographics. (n.d.). Association of Zoos & Aquariums | AZA.org. https://www.aza.org/partnerships-visitor-demographics?locale=en

IMAGE SOURCES

All images were taken by me during my visit to the Birch Aquarium or taken directly from the aquarium’s website: https://aquarium.ucsd.edu/.